|

Filed By:

Gabriel Ponniah, Editor In Chief Austin Alternative Screen Scene To the storyteller, sport is a useful tool. Sports provide an elegant structure and ready-made conflict, into which one can easily fit any number of characters or goals. Put simply, a spoonful of sport helps the narrative go down. I love me a good sports story, and fortunately Dogsville delivers just that. While it’s a little ‘ruff’ around the edges, this Canadian documentary feature provides an exciting look into the world of agility competition and teases at deeper ideological implications beneath the surface of this canine contest. Kirstin O’Neill makes for an endearing protagonist straight out the gate, as we’re introduced to the Canadian agility team. She’s scrappy and determined, matched only by the boundless enthusiasm of her dogs: aging legend Radical Rabbit, Posh Piranha, and the underdog mutt Crocodile Crunch. From regional qualifiers to international championships, we follow this motley crew on their aspirational journey to the top of the podium. Each trial, each tribulation, heartbreak along the way further imbues their struggle with pathos, building a strong narrative throughline. Though the Canadians take center stage in the film, the doc takes a wide view of the field at these dog-olympics. Each team possesses a character about it, often an echo of their national identity, and the filmmakers key in on this at every available opportunity. The Japanese team, for example, is portrayed as mild-mannered and genial, the Americans are well-funded, the Italians zealous, the Russians embattled—and so on and so forth. With ample coverage, what’s shown on screen feels very truthful to the events depicted, having left no stone unturned—no obstacle missed. But beyond the surface narrative lies a more compelling subtext: the plight of Crocodile Crunch. This classic David vs. Goliath story veers directly into an age-old distinction between purebreds and mutts. Conventional wisdom states that only purebreds have the pedigree to compete in agility contests—and to trainers, pedigree means a great deal. Mutts are believed to lack the innate intelligence and skill necessary for such challenges, but Crunchy aims to put such notions into the past. His success means a reevaluation of the status quo, a blow against the elitism present in the agility game and breeding at-large, and a win for nurture over nature. While Dogsville doesn’t shy away from this thread, its focus tends towards a different conflict: the perfection of animals versus the imperfection of humans. In its most effective moments, this examination is tremendously emotional, as when Radical Rabbit is carried off the competition floor after an injury derails his twilight run. But by and large, scrutinizing the handlers for their imperfections, especially in an international context such as this, can’t help but feel occasionally xenophobic. While the colorful picture painted of each nation’s identity may feel innocuous to the average viewer, veteran director Rosvita Dransfeld’s statement on the film is at-best tacit in some minor stereotyping, and at-worst trying to conjure sociopolitical conflict where none ought exist when she says she’s always “looking for creative and entertaining ways to paint a picture of the socio-political state of our world, reflecting on politics, economies and cultural developments. When I learned about the world of dog sports, I knew that I had found the perfect ‘parallel universe’ to reflect on National archetypes, and our boundless desire to win.” So, while it comes off as unsavory in this regard and isn’t able to follow through on tantalizing tidbits of classism, Dogsville nonetheless takes audiences on a sturdy and immersive trip to the host country of the Netherlands where our eyes are opened to the exciting, energetic, and entertaining world of agility. Filed By:

Gabriel Ponniah, Editor In Chief Austin Alternative Screen Scene The idea of “hyperobjects” has become prevalent in recent years—something “massively distributed in time and space, and so viscous—so sticky that it adheres to all that touch it,” according to popular science and philosophy YouTube channel Vsauce. Climate change qualifies as such an object, as well as holding the distinction of humanity’s greatest challenge in its history, as per many prominent thinkers and researchers. From Romania comes “we fly, we crawl, we swim: a short film about climate justice,” fully immersed in despair at the enormity of this most challenging hyperobject. The film blends several unconventional techniques resulting in a unique visual language distinct from any other animated film at AniFab. The incandescent line work, the layers upon layers of varying opacity, the gentle movement of elements, each adds to the film’s hypnotic nature, carried languidly forward by despondent narration that gives form to the occasional striking image of human cruelty. Director Aron Nor shows no lack of ambition in attempting to dismantle the notion of justice itself, challenge speciesism, and center animals in the climate change narrative. He’s successful to a point: the film sets out to ask how climate justice translates into an anti-speciesist framework, and at minimum, it does that. One wonders, however, at the efficacy of “we fly, we crawl, we swim,” as audiences new to the issue are unlikely to be moved to action by a film which so vilifies their perspective, and audiences already familiar with the messaging are liable to be lulled into a tearful slumber after 23 sorrowful minutes of runtime. It is nothing if not a downer—appropriate, perhaps, for a film whose subject is humanity’s ultimate downer, but as an essay, so-described by Nor, it lacks clarity and overcompensates with pathos. Much is lost in translation, I’m sure, and Nor and company seem to have done their research, but the end-result isn’t the rousing call to action that the film hopes—or indeed ought to be. Filed By:

Gabriel Ponniah, Editor In Chief Austin Alternative Screen Scene Once upon a time, there was a film festival. This festival focused on stories about animals. Projects were submitted from far and wide, focusing on exotic or endangered species. Some filmmakers had expertise and means to make big, sprawling projects, or journey to distant ecosystems for rare finds. Others used what they had around their home, drawing inspiration and resources from their own backyard, with no less potential for success than their globetrotting counterparts. “Wish” falls into the second category. Based on a true story, the short tells a fable of sorts about a young girl longing for companionship who adopts a stray dog into her New Mexico home. At just under 8 minutes, the film features abundant use of b-roll, perhaps in the hopes of immersing the audience in the world of the film. In the end, it manages a brief statement on the importance of proper adoption procedure. Filmmaker DezBaa’ (Sharon Anne Henderson) has extensive acting credits to her name, and grew up in a culturally rich environment, a citizen of the Navajo (Diné) Nation raised in the Española region of Northern New Mexico. A former geologist, the SAG actor has studied filmmaking at Northern New Mexico College and holds two MFAs from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, NM-one for Screenwriting and one for Creative Nonfiction. For all these credentials, and for all her admirable passion, the film falls flat on several fronts. “Wish” tends towards overreliance on title cards, which are best utilized when the footage itself tells a story and the words supplement that story. Much of the footage (framed with little regard to aesthetics, I might add) sits on the screen with a lack of narrative momentum, making 8 minutes into an eternity when run in a block which includes projects with professional weight behind them, or amateur works with more instinctual pacing. DezBaa’ drops a quote to begin her film about never working with children or animals, a famous adage in the industry for its truth. While much of that statement’s content is aimed at avoiding the production hassle these elements introduce, here “Wish” succumbs to a residual problem of the inclusion: the performances are wholly unconvincing (though reads from the adult working the clinic show little improvement). In defense of the on-screen talent, they certainly didn’t have much to work with in regards to the threadbare plot, as an efficient retelling of this story would charitably break the one minute mark. Film festivals like AniFab are beautiful in their unabashed combination of work from a broad spectrum of means and talent. Indeed, much of the meat behind the experience of attending the festival in-person was the teaching and learning—the collaborative, social process of becoming better filmmakers. Perhaps DezBaa’ can harness this power on future projects, learning from her professors, her contemporaries, and the wide array of talented individuals with whom I’m certain she’s come into contact during her time as a SAG actor. Filed By:

Gabriel Ponniah, Editor In Chief Austin Alternative Screen Scene The films at AniFab share one common thread: they are all “animal stories.” Some stick to that distinction more closely than others. While a great many are conservation-oriented with direct calls to action, particularly the documentaries, some narrative films enjoy more creative freedom in their implementation of the animal angle. The Man Who Forgot To Breathe is one of the more tenuous qualifications at AniFab 2021, but nevertheless tells an interesting story. Over the course of this Iranian film’s 15 minutes, we see a man staring abject solitude down the barrel as his wife prepares to leave him with their child, his anxiety rendered visually with the aid of his daughter’s pet goldfish by the metaphor of breathing. Writer/director Saman Hosseinuor cultivates a patient and methodical approach with carefully-framed, pensive cinematography and vacuous sound design that saves its flourishes for only a select few moments. It’s long for a short film, but never does the filmmaking lag. Without a word, his cast communicates so much through simple, yet effective looks, and Zanyar Lotfi gives us more still through his editing choices. Reinforcing the breathing motif by capitalizing on the respirator masks which so dominated the past year (and admittedly before then in more air-conscientious countries) is just icing on the cake. While it’s not likely to pique the interest of an animal advocate ahead of its AniFab contemporaries, The Man Who Forgot To Breathe is a quiet, subtly excellent character study more in line with traditional film festival fare. For those who tend towards more pensive, artistically-minded short films, this should be right in your wheelhouse. And who knows, perhaps Hosseinuor will expand upon his good instincts in future work. I certainly would be eager to see that come to fruition. Filed By:

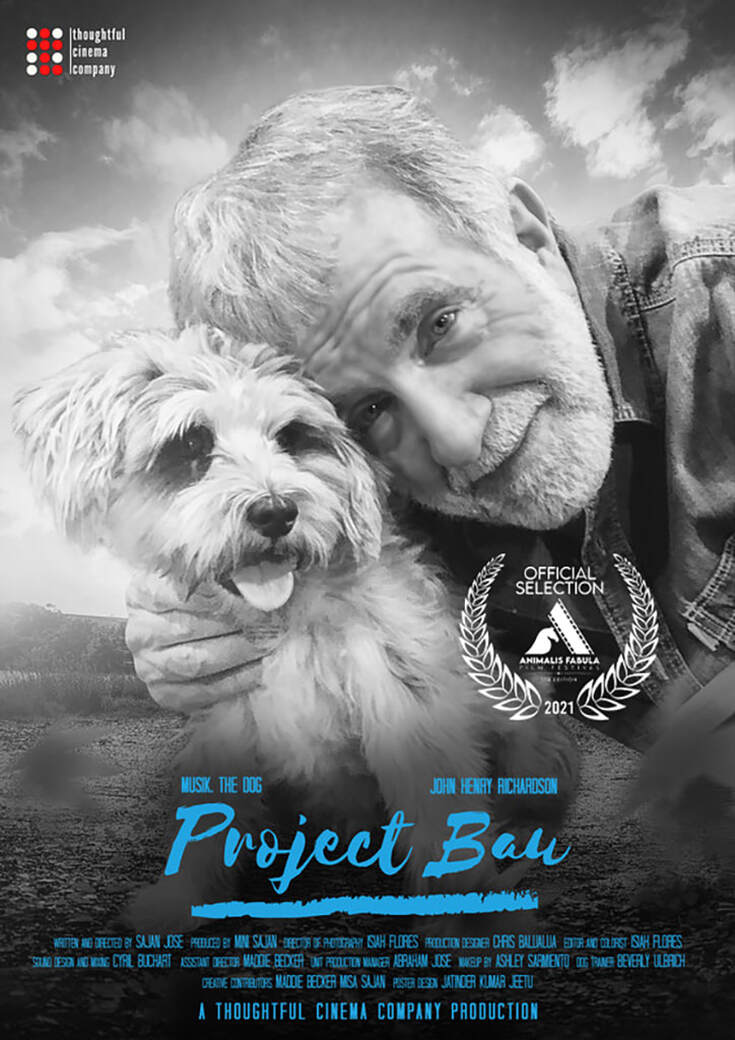

Gabriel Ponniah, Editor In Chief Austin Alternative Screen Scene Can you find man’s best friend at the bottom of a bottle? Project Bau asks that question through one of the more out-and-out narrative shorts in the AniFab rotation. In just shy of half an hour, we observe a desolate, elderly alcoholic isolated in the Sierra foothills, save for a regular trip into town to restock his liquor cabinet. But when a mysterious dog shows up outside his home, the pooch proves to be just what he needed to spur him back onto the wagon. The film boasts a sleek look with its ample use of drone and steadicam footage, washed thoroughly in a dramatic color palette. John Henry Richardson gives a lead performance as sturdy as his name, and the film’s high points are truly some of his character’s lows—reading the Into the Wild inscription from a presumably lost daughter, searching for a presumably lost Bau, grappling with his presumably lost sobriety. Despite these strengths, Project Bau certainly has room for improvement on the pre-production side. General wisdom with regards to short stories derives from the logic of Occam’s Razor—that every element be used to the peak of efficiency. With a limited time to deliver information, no word, no shot, no scene should be wasted. The best shorts often feature elements which accomplish multiple simultaneous goals—maybe they deliver characterization while also advancing the plot and establishing tone. Applying this level of scrutiny to the script for Project Bau would go a long way in tightening the final product. The short is overfull with tracking shots. Yes, they establish the disheveled way our star carries himself early on, but the message is received far before the tracking shots end. If embellished by distinct performances, such could be used to highlight the character’s arc, but even then they could be restrained in length. Speaking of arcs, there are glimpses of three act structure (an effective, if not strictly necessary screenwriting tool) in Project Bau—for example, the mailbox. Three is truly a magic number, and when the assumed third instance of an arc is omitted, it can leave the audience feeling unsatisfied, as if the mailbox was unimportant all along, and therefore wasted time. At over 25 minutes, Project Bau is too scant to be a feature, but long in the tooth for most shorts. Aside from the audience drain this produces, it’s also a challenge to program for festivals looking to assemble many shorts into a single feature length block. Trimming the fat would save Project Bau a lot of time. And what all could be done with that saved time? Perhaps Richardson could be afforded more screen time to build and live in the character; if he’s a strength, tailor the project to him. Perhaps a deeper examination of the nuances of alcoholism could arise, as the film’s current read of the situation is fairly straightforward. Perhaps the third act could be given more than a few seconds of resolution, as he searches in vain for Bau before finding another dog—perhaps there would’ve even been time to plant the idea of the second dog someplace in the first act so it doesn’t feel quite as arbitrary. Perhaps the whole thing should’ve ended in a solid 12 minutes with Richardson feeding Bau on the porch, just before that unfortunately commercial-sounding Lumineers-esque song wrongly colors an otherwise-serviceable montage. Ultimately, it’s up to the filmmakers. I had a lovely dinner with Sajan Jose, the writer-director of Project Bau, alongside other AniFab creators and attendees, and the most salient point of our conversation over KBBQ was the idea of film festivals as learning experiences—not only for the audience, but for the filmmakers, and in equal or often times greater measure. In hearing the discourse on the films at the festival, and more specifically the brainchildren of my tablemates, I had the privilege to witness the collaborative nature of filmmaking at work. And that’s what it’s all about, right? Filed By:

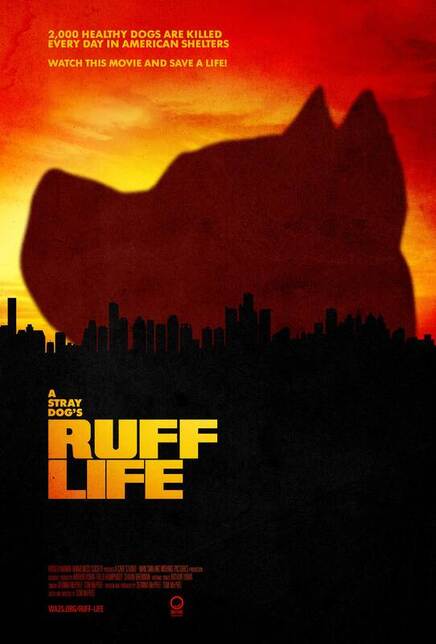

Gabriel Ponniah, Editor In Chief Austin Alternative Screen Scene Everybody loves dogs. They’re a convenient group to advocate for in that way—they’re almost fundamentally endearing. So when A Stray Dog’s Ruff Life sets its sights on the mistreatment of man’s best friend, it does so at its own peril. From early on in the documentary, images of neglected, emaciated mamas tending to their still-blind pups in a cozy corner of refuse raise an alarm in the back of viewers’ heads—the same alarm that compels a change of the channel when Sarah McLachlan starts singing “Angel.” And so it’s to the filmmaker’s credit that they avoid becoming mired in misery without shying away from the serious death and disease endemic to the crisis. By focusing on human efforts to combat apathy and bureaucracy, Ruff Life balances its tone while making its most effective point: the stray dog crisis across the country is no mere fact of circumstance, but could be changed for the better with improvements in communication and public policy. The filmmakers dive into the trenches with volunteer organizations, allowing for a ground-level view of the struggle to save these animals. Right off the bat, Detroit’s Pit Crew introduces the audience to their daily challenge,—in this case rescuing a mother and her puppies from abject homelessness within eyesight of the Michigan Humane Society, elegantly setting up the film’s main conflict between grassroots change and cumbersome bureaucracy. In Houston, too, the filmmakers follow local organizations like Houston Pets Alive and the city’s Best Friends Animal Society program as they combat Houston SPCA’s ineffectiveness along with other administrative shortcomings. To achieve these ends, the filmmakers employ a visual language that works on two fronts. Boots-on-the-ground video of activism at work in the field provides an intimate understanding of the problem and its many facets. Meanwhile, drone coverage interspersed throughout lends the film an affirming sense of scope and scale, appropriate for a project which tackles such a wide-ranging issue from multiple vantage points. Moving imagery of animals at both ends of the experimental spectrum—suffering in the wild as well as enjoying a dip at Barton Springs—captivates, and lines are drawn with powerful looks into the cruelty of bureaucracy. The incinerator smokestack connotes concentration camps, and an unsightly comparison awaits those who operate it further down this line of thinking. It’s important to remember, though, that there are humans who’ve chosen service as their vocation—on behalf of the public and/or their animal counterparts—on both sides of this issue. The filmmakers make clear the frame through which the audience is presented with this stray situation. Manipulative music and editing choices, as well as active efforts to catch subjects in awkward situations, are viable tools at the documentarian’s disposal, but ones which require scrutiny from viewers. Sure, former DACC Director Melissa Miller looks bad when accosted by the filmmakers’ investigation (one which apparently devolved from sit-down interview to guerrilla journalism at some point during production), but is she a harassing shill of an animal-hating administration or an under-equipped captain of an understaffed ship? The systemic flaws in animal control and public health deserve the ire of activists more than do employees caught in the system. Ask any Longhorn football fan if it’s possible to make meaningful change with three Directors in as many years, and they’ll lament the carousel of coaches who’ve so far failed to bring Texas back in each’s relatively brief tenure. Environmental factors, too, stymie the efforts of those working on behalf of the dogs. The film makes substantial use of Hurricane Harvey’s impact on their struggle, as well as highlighting different regional challenges when it comes to breeding. Already-overwhelmed facilities were understandably pushed beyond their administrative breaking point with the flooding that devastated Houston in 2017, and with the recent failure of ERCOT to provide Texans with power during a historic freeze, these environmental factors show no sign of easing up on a hemorrhaging system. Furthermore, it’s not solely their endearing quality which makes dogs a convenient group to advocate for. Dogs, believe it or not, can’t speak or organize, and naturally can’t be held accountable for their evolutionary programming when it comes to overpopulation. And their panting faces read to humans as smiling whether they’re delighted or miserable (a challenge noted by Houston volunteers rescuing a poor pooch stricken with mites). Communities don’t want to kill dogs, as say Dr. Jefferson and Ms. Hammond, but they don’t necessarily deserve to be shamed into oblivion for navigating an often cruel world as best they can. Though the filmmakers do well to insist their fight is with policies and systemic issues and not individuals (save the absent SPCA bigwigs), it’s easy to see how well-intentioned people get caught in the crossfire. The representatives who returned Ms. Vasquez’s dog aren’t responsible for the structural failures of Houston SPCA, and Ms. Vasquez insists it has nothing to do with them. But when they’re the ones facing down the confrontation, it’s hard to tell the difference. Ruff Life also falls short in another way. The filmmakers may well demonstrate their, ahem, dogged pursuit of the truth and root causes behind the crisis, but the documentary seems incurious as to the underlying culture which has produced such. The film sets up a case study between stray dog populations in Detroit and Houston. It promises a shocking discovery about the relationship between dogs on the street and those being killed in shelters. The filmmakers explore the process by which the former becomes the latter, as well as volunteer efforts to interrupt said process. Taking this direction achieves their intent—and it is a commendable one—but steers away from a more in-depth investigation. With Texas Governor Greg Abbott signing into law an effective criminalization of homelessness as of September 1st, it stands to wonder whether a State government which treats humans living unhoused in this way could muster any greater sympathy for its canine predicament. The same citizens who, say, don’t ‘believe’ in spaying or neutering an animal have recently been deputized by the Abbott administration to collect bounties on their fellow citizens for seeking abortions. Certainly, the comparison is unsightly, and perhaps the leap is too great to land gracefully, but interrogating these factors—especially with a regionally distinct point of comparison in Detroit—could’ve provided precious connective tissue while making more comprehensive their argument. On the whole, A Stray Dog’s Ruff Life makes a powerful statement and, complete with action steps peppered throughout its ending, has a chance at contributing to political change on behalf of dogs and their advocates everywhere. It’s appropriately brimming with frustration and celebration, as it takes a wide-reaching, if perhaps not deeply sociological, look into the stray crisis across America. If lack of communication is a pervasive systemic flaw in the care of stray animals, as the documentary suggests, then the film is a big step towards solving said flaw. If we’re to believe “the only way to make [people] care enough is to go into their homes,” then Ruff Life’s recent distribution deal with streaming-oriented 1091 Pictures has the chance to make people care indeed. |

Get tickets for any #AniFab22 screening:ATX Screen Scene

The ArchAngel of Austin Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed