Where Animal Stories Come To Life!

|

A Finely Curated Festival Of The Best Hand Selected Filmed Stories About Or Including Animals By Filmmakers From Around The World. #AniFab24 is Produced by the World Animal Awareness Society & WA2S Films, an award-winning Texas based 501c3 nonprofit charity

|

|

ANIMALIS FABULA FILM FESTIVAL * SUBMISSIONS NOW OPEN

A few of the #AniFab24 teasers of movies selected to date

AniFab selects about 5 projects per month for consideration to play during the live Animalis Fabula Film Festival in San Antonio in Nov.

|

|

|

|

#AniFab24, San Antonio's Animalis Fabula Film Festival has Partnered with AMC Theatres RiverCenter in Downtown San Antonio on the Riverwalk. Our Hotel is the Marriott RiverCenter attached to the theater. AniFab24 will feature cash prizes for the most outstanding movies in their respective categories. Filmmakers winning Monthly Best Of Fest Awards will have their films chosen to be presented at AniFab24 live and their accommodations paid for in San Antonio during AniFab24 as well as the opportunity to win a cash prize. Submit your movie on FilmFreeway!

Congratulations Shaunak Sen!

The Animalis Fabula Film Festival was proud to be your Texas Premiere!

Congratulations on all the accolades including Best Feature Documentary Oscar Nomination!

Congratulations on all the accolades including Best Feature Documentary Oscar Nomination!

And here's Texas Media Maker Editor In Chief Gabriel Ponniah's Full Review:

It can be difficult, growing up in today’s geopolitical “West,” to think of one’s self as anything other than an individual being, struggling to survive in a world markedly distinct from (and not altogether kind towards) our own life. But life, in fact, can be viewed through a fundamentally different lens. A swath of Eastern traditions, and thinkers working within them, have long championed a worldview which sees all life—the entire universe—as but one singular organism with many facets. Elements of this idea inform Eastern religious practices in Buddhist or Jainist customs, for example, but they were hardly exclusive to the continent of Asia. Nearly three centuries before the common era, the Greek philosopher Zeno, founder of the Stoic school of thought, declared “All things are parts of one single system, which is called Nature; the individual life is good when it is in harmony with Nature.”

You can read the All That Breathes review in its entirety here:

It can be difficult, growing up in today’s geopolitical “West,” to think of one’s self as anything other than an individual being, struggling to survive in a world markedly distinct from (and not altogether kind towards) our own life. But life, in fact, can be viewed through a fundamentally different lens. A swath of Eastern traditions, and thinkers working within them, have long championed a worldview which sees all life—the entire universe—as but one singular organism with many facets. Elements of this idea inform Eastern religious practices in Buddhist or Jainist customs, for example, but they were hardly exclusive to the continent of Asia. Nearly three centuries before the common era, the Greek philosopher Zeno, founder of the Stoic school of thought, declared “All things are parts of one single system, which is called Nature; the individual life is good when it is in harmony with Nature.”

You can read the All That Breathes review in its entirety here:

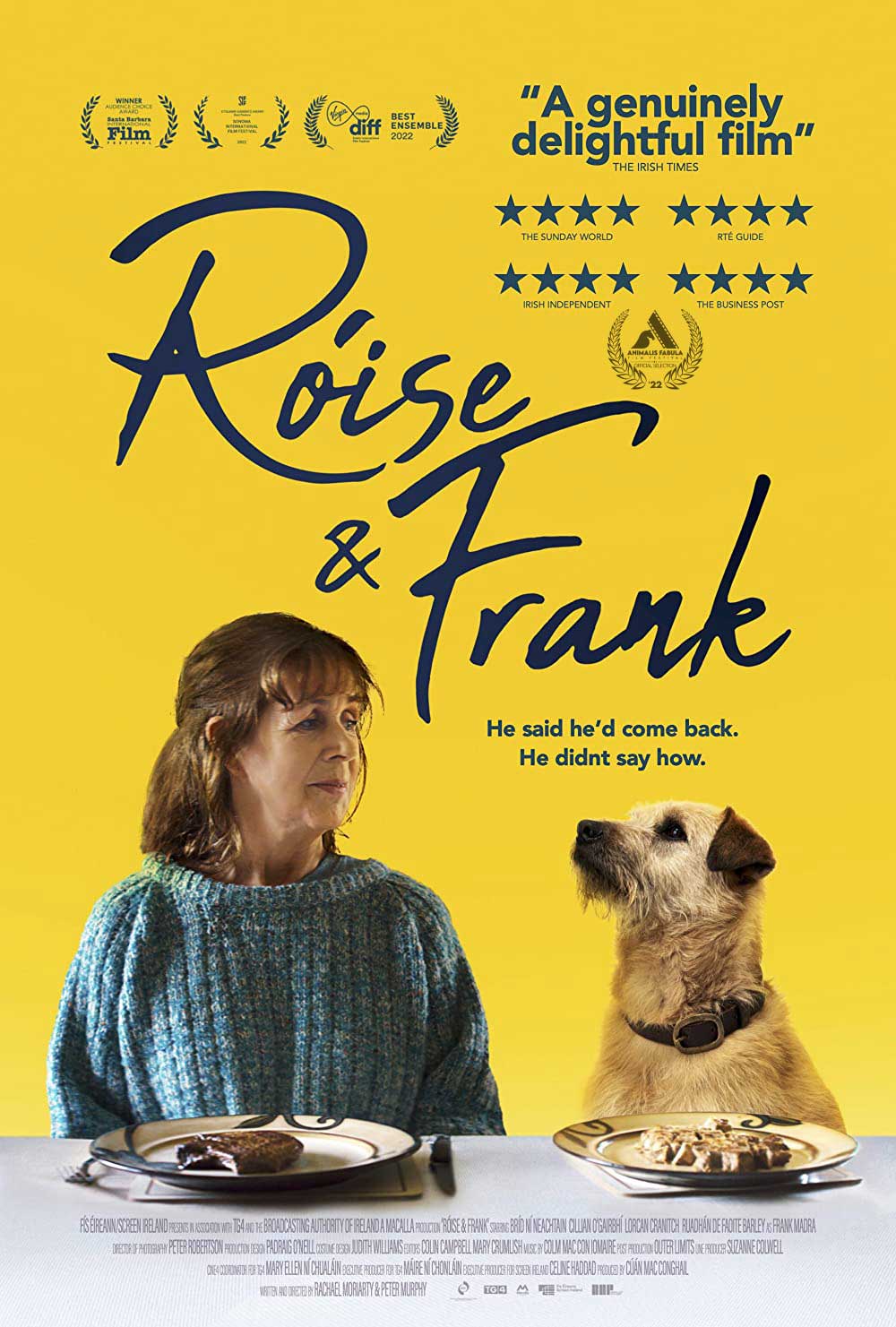

Congratulations Rachael Moriarty & Peter Murphy directors of RÓISE & FRANK

Animalis Fabula Film Festival, San Antonio's Best Narrative Feature Winner, Róise & Frank has received 6 Irish Film & Television Academy (IFTA) noms! Do we know how to pick 'em or what? Róise & Frank had it's #Texas Premiere at #AniFab22

If nothing else, what sets humans apart from nature is the extent to which they utilize the latter in service of the former. Whether working the land for agriculture or domesticating species purely for companion purposes, we’re able to weave wildlife into the very fabric of our lives. When my twin sister and I left home for college, my parents were, at once, empty nesters. To account for this sudden emptiness in the house, we were replaced with a dog—something to ease the transition from one phase of life to the next. Dogs are good in that way, eager to please. Róise & Frank takes this idea and runs with it, along the way exploring ideas about love, loss, reincarnation...and hurling. Read the entire review by Texas Screen Scene's Gabriel Ponniah here:

You Can't Walk The Red Carpet With An Award Unless You Submit On FilmFreeway!

"Participating in the Animalis Fabula Film Festival, aka #AniFab was like spending time with good friends. From the month's lead-up, to the three day event itself, festival director Tom McPhee's infectious enthusiasm in seeking to unite such a large and diverse group of film professionals together as a community was truly inspiring." The Conservation Game Team

"Animalis Fabula translates to animal story in Latin. If you have a film involving animals, this is a MUST fest to submit. Tom and his team are wonderful and passionate about what they do. They go out of their way to make filmmakers feel special. My film screened in person in a pandemic year which is challenging. But what a fun and powerful experience I had, being with like-minded compassionate people. I love details like my trailer playing in the theater lobby, festival signage and schedules in the hosting hotel, a dog in costume in the lobby and a guy in a bear suit. I would like to see this fest grow and get the attention it deserves. Again, a must if you have an animal film. And if you like a film festival that feels like camp, this is it! I made great new friends here." Mye Hoang, Award-Winning Director of Cat Daddies

|

Texas Media Maker Editor In Chief Gabriel Ponniah Interviews Esmeralda Hernandez, Director of Outstanding Achievement in Live Action Short, Dream Carriers

|